Hardly a day goes by without a call from an ISO, merchant, or processor who asks us for help in finding someone to process ACH transactions. There is usually some urgency in these requests – we can hear it in their voice. This is partly because of the customary and normal positioning by the ISO to handle all payments for the merchant:

Hardly a day goes by without a call from an ISO, merchant, or processor who asks us for help in finding someone to process ACH transactions. There is usually some urgency in these requests – we can hear it in their voice. This is partly because of the customary and normal positioning by the ISO to handle all payments for the merchant:

- ACH

- Credit and debit cards

- Loyalty

You want your merchants to see you as their payments expert. Merchant attrition typically runs about twenty percent, but when the merchant thinks of you as an expert instead of a commodity, you can bring this number much lower, which does a lot for the value of your portfolio.

Let’s start by defining what an ACH transaction is, along with a bit of history. First, let’s put aside the mistaken notion that check processing is inefficient and that ACH is a better way to process payments. Actually, check processing, particularly with Check 21, is a highly efficient operation. It’s not about that.

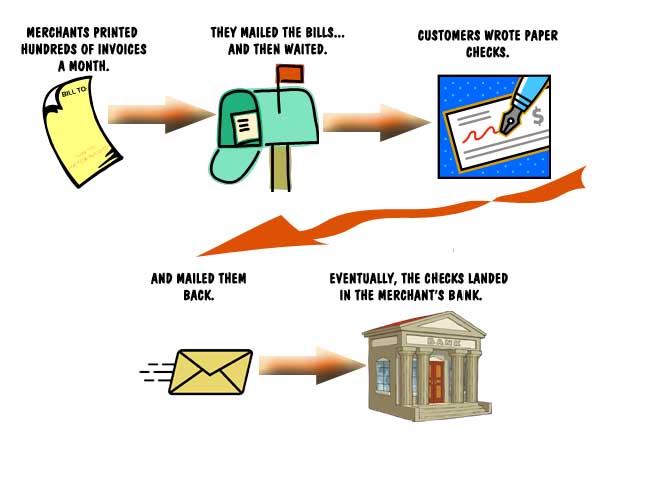

The impetus for an ACH recurring debit authorization came from very large billers, such as insurance companies, that were printing and mailing millions of bills a month, then waiting for the consumer to get the bill, write a check, and mail it back to their lock box for posting and deposit.

This is what is called the Cash Management Time Line. You can readily see that this might be a thirty day or longer payment cycle, and the cost of printing and mailing all those bills and maintaining the lock box would be in the millions of dollars a year for a large enterprise. Not to mention the time value of the cashflow and the sheer amount of work in the process.

This is what is called the Cash Management Time Line. You can readily see that this might be a thirty day or longer payment cycle, and the cost of printing and mailing all those bills and maintaining the lock box would be in the millions of dollars a year for a large enterprise. Not to mention the time value of the cashflow and the sheer amount of work in the process.

ACH started with the idea that a large insurance company could get almost all of its customers to sign an authorization for a recurring monthly debit to their checking accounts. I remember when I signed up for my life insurance policy – the agent told me that I was required to sign the authorization to get coverage!

Now, instead of printing and mailing all those bills and waiting to get paid, the insurance company, called the “Originator,” creates a file in a standard format that all banks can understand, sends the file two days before the settlement date to the bank (called the “Originating Depository Financial Institution,” or ODFI), which sends the file out through the Fed or through the clearinghouse to the consumer’s bank (called the “Receiving Depository Financial Institution,” or RDFI), which then debits the consumer’s checking account (the “Receiver”) on settlement day. The consumer would see this debit on his statement, or on the home banking report, but he would not see the information that appears on the face of the check because the processor has only the MICR line. There is no check number either, with an ACH.

The rules for these transactions were written by a banking industry trade association called The National Automated Clearinghouse Association, or NACHA. NACHA is not a government agency; it is really run by the very largest issuing banks, but any bank can join. NACHA is not a regulator, but it does write the rules that the real regulators (the FDIC) use when they analyze a bank. I have a copy of the NACHA Rules and Regs on my desk and it is a pretty hefty tome that runs into the hundreds of pages, and it is not easy to read either.

The rules for these transactions were written by a banking industry trade association called The National Automated Clearinghouse Association, or NACHA. NACHA is not a government agency; it is really run by the very largest issuing banks, but any bank can join. NACHA is not a regulator, but it does write the rules that the real regulators (the FDIC) use when they analyze a bank. I have a copy of the NACHA Rules and Regs on my desk and it is a pretty hefty tome that runs into the hundreds of pages, and it is not easy to read either.

Unlike checks, which are governed by check law and the Uniform Commercial Code, NACHA is governed by its own rules and Regulation E, which is a consumer protection statute. This is the heart of the matter, because Reg. E gives the consumer 60 days to dispute a transaction, so the merchant does not have finality of payment for 60 days. Unlike a check, where there are very few defenses to payment, there are many return reason codes in the ACH world. When the merchant deposits a check, he does not have to prove that the consumer authorized the check – the signature on the check does this. In the ACH world, the merchant must have a signed authorization by the consumer, or there has to be a notice conspicuously placed that tells the consumer that his check may be converted to an ACH. If the merchant cannot prove authorization or notice, the consumer has a valid defense to payment.

And this is the heart of the matter, because consumers can and do dispute ACH debits to their accounts. This is not a problem for very large billers, such as public utilities, phone companies, cable companies, health clubs, etc. But it is a problem in what used to be called the “Card Not Present” space. These are Internet, telephone, or mail order-catalog merchants. The difficulty for these merchants is proving that the consumers are who they say they are, because they are not present. In these circumstances, the consumer can say that he didn’t authorize the transaction, or some other generalized grievance which would not pass muster in the check world. NACHA does not want to see this number even get close to one percent, which is a pretty narrow margin for error. If this happens, the ODFI is “persuaded” by NACHA to terminate the merchant. It is very difficult for the merchant to ever recover from this situation, kind of like being on the Terminated Merchant File. If NACHA suspects that a bank is signing up merchants with higher than normal returns, this can lead to regulatory pressure on that bank to get out of the ACH processing business.

Effective June, 2010, NACHA rules require all banks to conduct an ACH risk assessment and to implement risk management programs based on the results of the assessment. The rules focus on the potential risks of origination services to separate business and institutional originators. This includes such things as the following:

- ACH compliance audit

- Exception handling

- Money laundering activity

- Origination services policies, particularly for third party senders or telephone/Internet authorizations

- Origination agreements

Third party senders, also called Third Party Processors (TPP), are a big part of the ACH world because they were the ones who stepped up to the plate in the early days of ACH, when banks did not want to sign up merchants themselves. Current rules require the bank to review the financial and operational status of the TPP, and there should be a vendor management program with guidance on investigating credit risk and operational risk issues at each TPP. ACH risk is comprised of operational risk, fraud risk, and credit risk.

The other key to the puzzle is that ACH processing for a bank is a penny business, literally. There is no pricing for risk, so it costs a few cents to send a transaction, whether for fifty dollars or five million dollars. Per transaction pricing is so low that it is almost impossible for a bank to make real money or even an acceptable return on expense in ACH processing without very large volume. So, if you were the banker, why would you do this, except for your very best customers who were right in your market area? Since June, 2010, the answer is, increasingly, you wouldn’t. And that’s why some merchants have difficulty finding an originating bank.